This section provides some basic reference notes on the core Jena RDF API. For a more tutorial introduction, please see the tutorials.

In Jena, all state information provided by a collection of RDF triples is

contained in a data structure called a Model. The model denotes an

RDF graph, so called because it contains a collection of RDF nodes,

attached to each other by labelled relations. Each relationship goes

only in one direction, so the triple:

example:ijd foaf:name "Ian"

can be read as 'resource example:ijd has property foaf:name with value "Ian"'.

Clearly the reverse is not true. Mathematically, this makes the model an instance of a

directed graph.

In Java terms, we use the class Model as the primary container of RDF information

contained in graph form. Model is designed to have a rich API, with many methods

intended to make it easier to write RDF-based programs and applications. One of

Model's other roles is to provide an abstraction over different ways of storing

the RDF nodes and relations: in-memory data structures, disk-based persistent stores

and inference engines, for example, all provide Model as a core API.

While this common abstraction is appealing to API users, it is less convenient when trying

to create a new abstraction over a different storage medium. For example, suppose we

wanted to present an RDF triples view of an LDAP store by wrapping it as a Jena Model.

Internally, Jena uses a much simpler abstraction, Graph as the common interface to

low-level RDF stores. Graph has a much simpler API, so is easier to re-implement

for different store substrates.

In summary there are three distinct concepts of RDF containers in Jena:

Model, a rich Java API with many convenience methods for Java application developersGraph, a simpler Java API intended for extending Jena's functionality.As an application developer, you will mostly be concerned with Model.

So if RDF information is contained in a graph of connected nodes, what do the nodes themselves

look like? There are two distinct types of nodes: URI references and literals. Essentially, these

denote, respectively, some resource about which we wish to make some assertions, and concrete data values that

appear in those assertions. In the example above, example:ijd is a resource, denoting a person,

and "Ian" denotes the value of a property of that resource (that propertly being first name, in this case).

The resource is denoted by a URI, shown in abbreviated form here (about which more below).

What is the nature of the relationship between the resource node in the graph (example:ijd) and

an actual person (the author of this document)? That turns out to be a surprisingly subtle and

complex matter, which we won't dwell on here.

See this very good summary of the issues

by Jeni Tennison for a detailed analysis. Suffice to say here that resources - somehow - denote

the things we want to describe in an RDF model.

A resource represented as a URI denotes a named thing - it has an identity. We can use that identity

to refer to directly the resource, as we will see below. Another kind of node in the graph is a literal,

which just represents a data value such as the string "ten" or the number 10. Literals representing

values other than strings may have an attached datatype, which helps an RDF processor correctly

convert the string representation of the literal into the correct value in the computer. By default,

RDF assumes the datatypes used XSD are available, but in fact

any datatype URI may be used.

RDF allows one special case of resources, in which we don't actually know the identity (i.e. the URI) of the resource. Consider the sentence "I gave my friend five dollars". We know from this claim that I have friend, but we don't know who that friend is. We also know a property of the friend - namely that he or she is five dollars better off than before. In RDF, we can model this situation by using a special type of resource called an anonymous resource. In the RDF semantics, an anonymous resource is represented as having an identity which is blank, so they are often referred to as nodes in the graph with blank identities, or blank nodes, typically shortened to bNodes.

In Jena, the Java interface Resource represents both ordinary URI resources and bNodes (in the case

of a bNode, the getURI() method returns null, and the isAnon() method returns true).

The Java interface Literal represents literals. Since both resources and literals may appear

as nodes in a graph, the common interface RDFNode is a super-class of both Resource and Literal.

In an RDF graph, the relationships always connect one subject resource to one other resource or one literal. For example:

example:ijd foaf:firstName "Ian". example:ijd foaf:knows example:mary.

The relationship, or predicate, always connects two nodes (formally, it has arity two). The first argument of the predicate is node we are linking from, and the second is the node we are linking to. We will often refer to these as the subject and object of the RDF statement, respectively. The pattern subject-predicate-object is sufficiently commonplace that we will sometimes use the abbreviation SPO. More commonly, we refer to a statement of one subject, predicate and object as a triple, leading naturally to the term triplestore to refer to a means of storing RDF information.

In Jena, the Java class used to represent a single triple is Statement. According to the RDF

specification, only resources can be the subject of an RDF triple, whereas the object can be a

resource or a literal. The key methods for extracting the elements of a Statement are then:

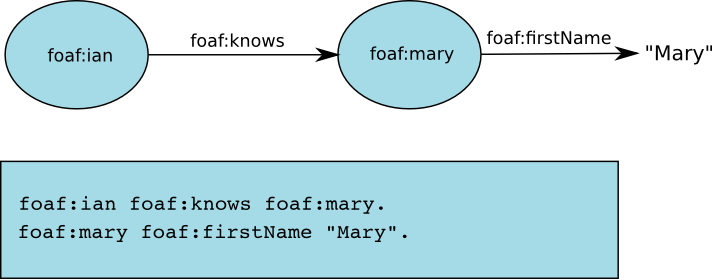

getSubject() returning a ResourcegetObject() returning an RDFNodegetPredicate() returning a Property (see below for more on Properties)The predicate of a triple corresponds to the label on an edge in the RDF graph. So in the figure below, the two representations are equivalent:

Technically, an RDF graph corresponds to a set of RDF triples. This means that an RDF resource can only be the subject of at most one triple with the same predicate and object (because sets do not contain any duplicates).

As mentioned above, the connection between two resources or a resource and a literal in an RDF graph

is labelled with the identity of the property. Just as RDF itself uses URI's as names for resources,

minimising the chances of accidental name collisions, so too are properties identified with URI's. In fact,

RDF Properties are just a special case of RDF Resources. Properties are denoted in Jena by the Property

object, which is a Java sub-class of Resource (itself a Java sub-class of RDFNode).

One difference between properties and resources in general is that RDF does not permit anonymous

properties, so you can't use a bNode in place of a Property in the graph.

Suppose two companies, Acme Inc, and Emca Inc, decide to encode their product catalogues in RDF. A key

piece of information to include in the graph is the price of the product, so both decide to use a price

predicate to denote the relationship between a product and its current price. However, Acme wants the

price to include applicable sales taxes, whereas Emca wants to exclude them. So the notion of price

is slightly different in each case. However, using the name 'price' on its own risks losing this

distinction.

Fortunately, RDF specifies that a property is identified by a URI, and 'price' on its own is not a URI. A logical solution is for both Acme and Emca to use their own web spaces to provide different base URIs on which to construct the URI for the property:

http://acme.example/schema/products#price http://emca.example/ontology/catalogue/price

These are clearly now two distinct identities, and so each company can define the semantics of the price property without interfering with the other. Writing out such long strings each time, however, can be unwieldy and a source of error. A compact URI or curie is an abbreviated form in which a namespace and name are separated by a colon character:

acme-product:price emca-catalogue:price

where acme-product is defined to be http://acme.example/schema/products#. This can be defined,

for example, in Turtle:

@prefix acme-product: <http://acme.example/schema/products#>. acme-product:widget acme-product:price "44.99"^^xsd:decimal.

The datatype xsd:decimal is another example of an abbreviated URI. Note that no @prefix rules

are defined by RDF or Turtle: authors of RDF content should ensure that all prefixes used in curies

are defined before use.

Note

Jena does not treat namespaces in a special way. A Model will remember any prefixes defined

in the input RDF (see the PrexixMapping

interface; all Jena Model objects extend PrefixMapping), and the output writers which

serialize a model to XML or Turtle will normally attempt to use prefixes to abbreviate URI's.

However internally, a Resource URI is not separated into a namespace and local-name pair.

The method getLocalName() on Resource will attempt to calculate what a reasonable local

name might have been, but it may not always recover the pairing that was used in the

input document.

can be used as the subject of statements about the properties

of that resource, as above, but also as the value of a statement. For example, the property

is-a-friend-of might typically connect two resources denoting people

As a guide to the various features of Jena, here's a description of the main Java packages.

For brevity, we shorten com.hp.hpl to chh and org.apache.jena to oaj.

Important note At some future point, now that Jena has become a project under the Apache

Software Foundation, the package names beginning com.hpl.hpl will change to org.apache.

We will provide transition packages to help Jena users adapt to this

change when it occurs.

| Package | Description | More information |

|---|---|---|

| chh.jena.rdf.model | The Jena core. Creating and manipulating RDF graphs. | |

| oaj.riot | Reading and Writing RDF. | |

| chh.jena.datatypes | Provides the core interfaces through which datatypes are described to Jena. | Typed literals |

| chh.jena.ontology | Abstractions and convenience classes for accessing and manipluating ontologies represented in RDF. | Ontology API |

| chh.jena.rdf.listeners | Listening for changes to the statements in a model | |

| chh.jena.reasoner | The reasoner subsystem is supports a range of inference engines which derive additional information from an RDF model | Reasoner how-to |

| chh.jena.shared | Common utility classes | |

| chh.jena.vocabulary | A package containing constant classes with predefined constant objects for classes and properties defined in well known vocabularies. |

chh.jena.xmloutput | Writing RDF/XML. | I/O index